Chains of Addiction

“Each day blurred into the next, filled with panhandling and gulping down cheap vodka.”

Remorse swept over a wasted John Donovan during a rare moment of clarity: “Jack’s seven tomorrow. I’m not there again. My son needs me.”

The lament surprised John. “When you’re a chronic alcoholic, you get to where you can no longer love. You lose the ability for emotions. You become mentally ill. Everything’s about the next bottle. That was me.” April 1986 marked rock bottom for John. He had been strung out, begging on the streets of Chicago for two full years. He describes that terrifying time as “a living hell of despair, hopelessness, blackouts and non-stop boozing.”

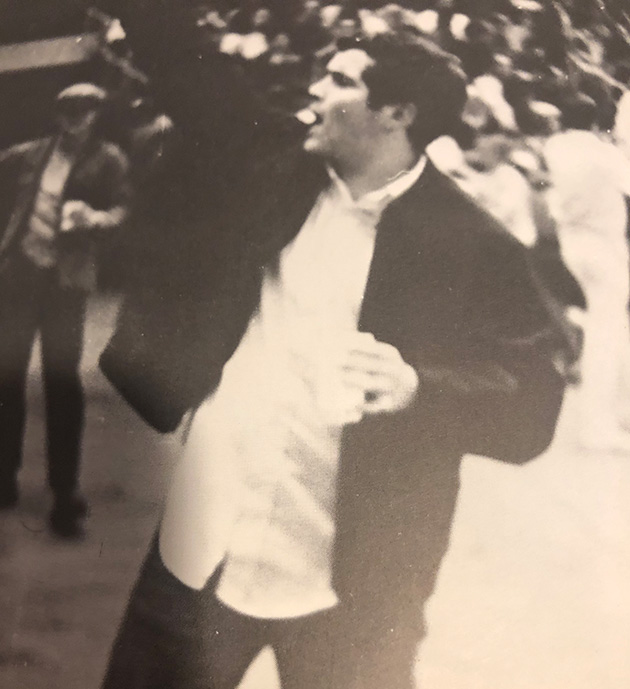

John’s life began in 1948 with great promise. He and his three siblings, born into an affluent Long Island, NY family, lacked for nothing. His father was a dentist. His nurturing housewife mother taught her children to love God and respect others. All four kids received Catholic educations.

The drinking started when he was a high school senior. It accelerated upon moving to San Antonio, TX to attend St. Mary’s University. Initially he disliked the taste of liquor but felt it had a positive socializing effect. “Frat life turned into a bona fide Animal House,” John muses. During a classroom lecture on alcoholism, he remembers thinking, “That will never happen to me. I only drink to party with my friends!”

After graduation, John joined the Peace Corps. He learned Spanish and was assigned as a physical education teacher and soccer coach at a small Catholic school in Venezuela. There he met Beth, another Peace Corps volunteer.

When his stint in the Peace Corps ended, an opportunity opened in food service management, requiring relocation to Chicago. John married Beth and fathered a son and two daughters. His skills led to another opportunity when Jim McHugh, a business associate, asked John to become his partner, creating the Donohugh Food Brokerage Company. The young firm expanded quickly, providing John’s family with a comfortable living and a new home in an upscale suburb.

But the dream didn’t last. John’s drinking spiraled out of control. His poison, exclusively beer and vodka, caused him to lose everything—business, home and family. He says, “In early 1984, I just ‘disappeared’ one day and found myself destitute; not living, but dying, on the streets of Chicago.”

Each day blurred into the next, filled with panhandling and gulping down cheap vodka with every dollar John could get his hands on. He racked up warrants for drunk and disorderly conduct and spent time in Cook County jail.

At first, John had a vehicle, but it was stolen during one of his blackouts. As he deteriorated, he faced seizures, hallucinations, esophageal hemorrhaging, abdominal swelling from cirrhosis of the liver, Hepatitis B, a coma and a stay at Manteno State Psychiatric Hospital. He suffered numerous facial injuries from falling flat onto sidewalks. One day, he fell onto the Howard Street El tracks, cracking open his skull. He died and left his body but was revived in the ER.

Chicago winters were relentless. John slept on bare floors of courtyard apartment building vestibules. Desperate, he sought assistance from several social service agencies. Dedicated, caring personnel tried to help him, but to no avail. When someone suggested The Salvation Army, he resisted. He was afraid it might ruin his reputation. The Army was for low-class bums, whereas he was a “better class” of bum.

Then came rock bottom. John was working the luggage carts for change at O’Hare Field when he noticed the date on a screen and realized it was Jack’s birthday. An inner voice nudged him: “Call The Salvation Army.” “It was a God thing,” John insists. Sergeant-Major Walter McClintock answered the phone. “We’ve been waiting for your call John. Let’s talk.”

John engaged in an act of repentance and faith. He threw his last bottle of vodka into the garbage before arriving at the Harbor Light Corps. As the door opened, John encountered steep stairs to the lobby. A transformation occurred reminiscent of earlier days in Salvation Army history when drunkards at open-air meetings knelt inebriated at the drumhead and rose completely sober. While climbing the stairs, John experienced God’s grace. He states, “I can’t explain it. Words are paltry but when I reached the top, the desire to drink was gone forever!”

John’s year at the Harbor Light was sobering. In detox, his body underwent horrific withdrawal symptoms. Then came an intense rehab routine lasting one month. Via counseling, 12-step meetings, worship and prayer at the Mercy Seat, John experienced more divine graciousness through Jesus Christ, relearning and strengthening the spirituality his mother once desired for him.

Life at the Harbor Light was a healing balm. “I was treated with love and respect—something that was non-existent on the streets. Most people treat addicts with disdain, when in fact, the addiction is a disease and should be handled as such.”

Yet paradoxically, he takes full responsibility for his own wrongdoing too. He believes that the spiritual component of the Army’s program was the actual “medicine” that cured the deepest aspects of his addiction.

“Addiction starts as a physical disease but if allowed to progress, soon consumes the total person—body, soul and spirit. It quickly becomes a spiritual disease destroying relationships (see sidebar). Hence comes a personal need for repentance—turning from sin and finding restoration,” John says.

After the rehab period, clients were allowed to live and participate at the center while working day jobs on the outside. John obtained work as a waiter at a posh private club. He slowly restored the broken relationships with his wife and children. One day, he returned home for good.

John testifies: “I’m forever grateful to The Salvation Army for saving my life by showing me, again, my need for God. I now rest in the promise that nothing can ever separate me from His eternal love through Jesus Christ our Lord” (Romans 8:38-39).

Success

The miracle of John Donovan’s sobriety continues. He still attends and leads local and international (via Zoom) 12-step meetings. In 1987 John founded another food brokerage, representing large food companies for the sale of their products in Illinois and Wisconsin. Now retired, his son Jack is CEO.

John and Beth’s daughter Anne is an executive in Colorado and married. Their daughter Kate, who has Down syndrome, lives at Misericordia Home in Chicago and visits her parents on weekends. They also have four grandchildren.

John verbalizes his undying affection for Beth. “She’s my great love. No one could ask for a better life partner!” They contribute financially to and volunteer for several charitable concerns spanning the Chicago area and South America. For years John served as chairman of the Chicago Harbor Light Advisory Board. A Catholic, he attends Mass with Beth on Saturdays, and in addition worships on Sunday mornings at The Salvation Army Oakbrook Terrace Corps. He volunteers at the corps throughout the week.

John corrects people who mistakenly assume he’s “successful” because of his present wealth. He states that temporal things—money, possessions, position, even philosophical attempts to find meaning in life through the cycles of nature—are not where true success and significance are found.

He believes Scripture nails it. (Deut.6:5; Matt. 22:37; Mark 12:30) True success and profound meaning in life is achieved through deeply fulfilling relationships with God and others.

John is emphatic. “If it weren’t for God’s grace I wouldn’t be here. Period. I’d be dead; a wasted, twisted soul, adrift and unprepared for eternity.”

Daryl Lach of Lisle, IL is a soldier at the Oakbrook Terrace Corps. He is a respected writer, having contributed articles to The War Cry and other Salvation Army periodicals.