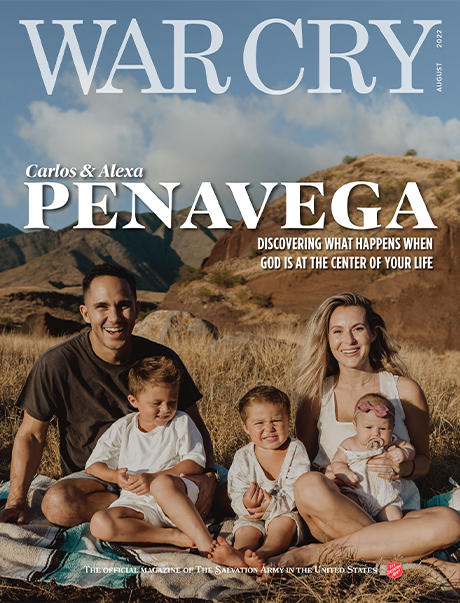

Side by Side with Corrie ten Boom

Two women who took risks to spread the gospel.

Rarely do people choose to go to jail. In 2003, Ellen Stamps entered the Richmond, VA jail in search of something familiar. A recent retiree, she was drawn there because of the many visits she made to similar prisons during the nine years she worked with Corrie ten Boom.

On her first day, the lead chaplain warned Ellen to be careful amongst the group he had assigned to her. Anything, she was told, could become a projectile. She decided not to worry before seeing what she was getting into.

Ellen descended the metal stairs down to the bottom of the building where individual cells housed the inmates. Two barriers separated the guards from the female occupants. She wondered, “How can I talk personally to the women?” She asked the guard to remove the barriers so she could be closer to the inmates. Miraculously, he did, and he let Ellen go from one cell to the next, meeting each inmate face to face.

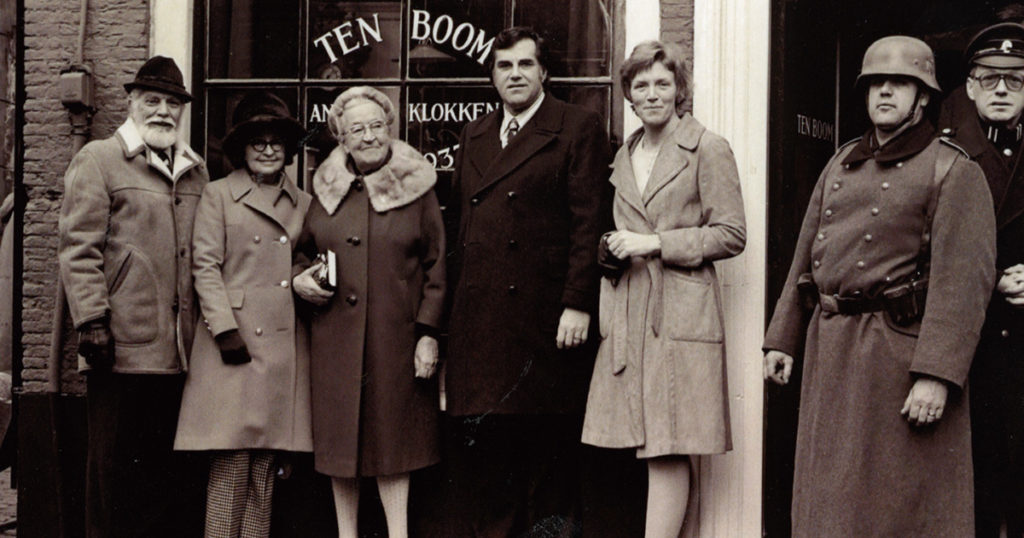

Ellen was no stranger to taking risks for the sake of the gospel. For nearly a decade, she ministered alongside the world-renowned evangelist and bestselling author Corrie ten Boom. December 30, 2024 will mark the 80th anniversary of Corrie’s release through a clerical error from the Ravensbrück Concentration Camp near Berlin, Germany. Corrie was arrested on February 28, 1944, with five members of her family, during the Nazi occupation of the Netherlands. Her crimes were hiding Jews in her family home and arranging for hundreds of other hiding places across the country.

“The Hiding Place,” an international bestseller published in 1971, is an autobiographical account of Corrie’s life and imprisonment. For 53 years, the account of Corrie’s courage and trust in God has inspired millions worldwide. In 1967, Ellen de Kroon began working for Corrie, accompanying her on what was, even before the publication of “The Hiding Place,” an increasingly full itinerary of speaking engagements and appearances—one she describes in her book, “My Years with Corrie.”

Ellen’s first trip with Corrie was to Israel in 1968 when the Israeli government honored Corrie at Yad Vashem, planting a tree in the Garden of the Righteous in recognition of her work during the Holocaust. Subsequent trips would take Ellen to less hospitable places. Their trip to Moscow later that year was not Corrie’s first behind the Iron Curtain, nor her last.

In Moscow, secret police kept them under constant observation. Corrie would not speak or preach but would “bring greetings from the people of the Netherlands,” always somehow inserting a Bible story into her greeting. The threat of being imprisoned or causing someone else to be imprisoned loomed over Corrie and Ellen. “The scary part was always that you [might] bring someone else difficulties. But they wanted Bibles for the people. They didn’t care about the danger. And there were so many people that were imprisoned for being an open book.” Corrie, who learned at Ravensbrück the surpassing value of a smuggled-in Bible, endeavored to provide the same gift to many.

Ellen still vividly remembers the lengths to which they would go to get Christian literature to the people: “We went to Prague with a car filled with contraband supplies. And, you know, we could have been in big trouble. But I was a nurse, and I would say to the police, ‘I am a nurse, and I can help.’ They never checked our cars. And so, we drove on, and we went to the people we knew, and we gave the Bibles to a certain person.”

Ellen’s description of making deliveries to the underground church belongs to the Cold War era, only perhaps in a spy thriller rather than a missionary’s journey: “I would be seated. We see each other in the park. I have a black suitcase, and you have the same suitcase. That was already organized. You don’t put anything in your suitcase, but while you’re talking and standing up, I take your suitcase, and you take mine. So, everything had to be organized. And I knew all these things.”

Ellen had many other harrowing experiences with Corrie. The duo would smuggle Bibles and other Christian literature into places like Cuba, Tajikistan, Uzbekistan, and Kazakhstan. In Cuba, customs interrogated them about the books in their luggage. Corrie simply indicated they were books she wrote and offered the customs officer an autographed copy. He then waved them through without further inspection. In Kazakhstan, while walking to visit a Christian couple, Ellen felt they were being followed, which was the norm in Communist countries. She bent down to tie Corrie’s shoes and saw through her legs two men who quickly darted off. They stopped, sat on a bench outside a farmhouse and waited. Eventually, the two men passed by. Having been followed all day, Corrie and Ellen decided against reaching their intended destination.

At the Richmond jail some three decades later, Ellen entered her new ministry space undeterred by the warnings she had received. She felt at home in the jail-perhaps because of her extraordinary experiences with Corrie. When she walked into the room full of inmates, she saw on the table something unexpected: her book, “My Years with Corrie.”

She asked who had read that book. The women indicated they had and that it was a book about Corrie ten Boom and her helper. “Girls,” Ellen replied, “It’s me, and I’m visiting you all.” For five years, Ellen met them there. “I could take them out of their little holes, and I had my own little open hall where we could sit together, and we had privacy. It was the best. Oh, I love that ministry.”

In 1976, Ellen’s travels with Corrie ended after nine years of fruitful service. She had fallen in love and moved to Oklahoma after marrying her husband, Bob Stamps. Corrie’s life would continue to intersect with Ellen’s. At her wedding in Holland, Ellen had missed Corrie. At the reception, she was then surprised to hear a recording of Corrie greeting the newlyweds. In 1977, Corrie attended the baptism of Bob and Ellen’s son, Peter John. Just six years later, on her 91st birthday, Corrie went to Heaven.

Through the years, Corrie ten Boom gave Ellen several gifts, including a painting by A. Miolée, the Dutch artist, with a note inscribed on the back, which read:

To Ellen de Kroon from Tante Corrie:

As a little remembrance of the blessed years that we wandered together as fellow tramps for the Lord in many countries. It is great to know that whatever we do in love for the Lord is never lost and never wasted.

1 Corinthians 15:58.

Corrie ten Boom

On a recent visit to Bob and Ellen’s home in Richmond, I saw this note, which Ellen describes receiving in her book. I’ve also seen another of Corrie’s gifts to her former secretary, a Friesian clock that belonged to the ten Boom family for 150 years. Corrie’s father, Casper, often reminded her “not to ever let the Friesian clock run down.” Before the family was taken into custody, the last thing he did was pull the weights on the clock. He would die 10 days later in prison.

I suppose it is no surprise that a family of clockmakers should make such efficient use of their time. Following her miraculous release from Ravensbrück and, six months later, the end of the Second World War, Corrie ten Boom spared no time beginning her reconciliation and evangelistic efforts. Across the entire span of her life, one finds astonishing instances of her immediacy to do “in love for the Lord,” knowing that any such action is “never lost and never wasted.” Ellen’s life also displays this holy immediacy, answering God’s call to love, especially in places where few would choose to go, loving people sorely in need of God’s love.

Clocks can help us measure time in more ways than one. I recently inherited a grandfather clock following my grandmother’s promotion to Glory. It sounds a line of the Westminster Chimes every 15 minutes and its entirety on the hour. One night, the clock played its song, and I thought of the “tramps for the Lord”—two women “contending side by side for the faith of the gospel” (Phil. 1:27). The words to the tune read:

All through this hour,

Lord, be my guide

That by thy power

No foot shall slide.